A marine mammal toxicologist weighs in on the microplastic crisis

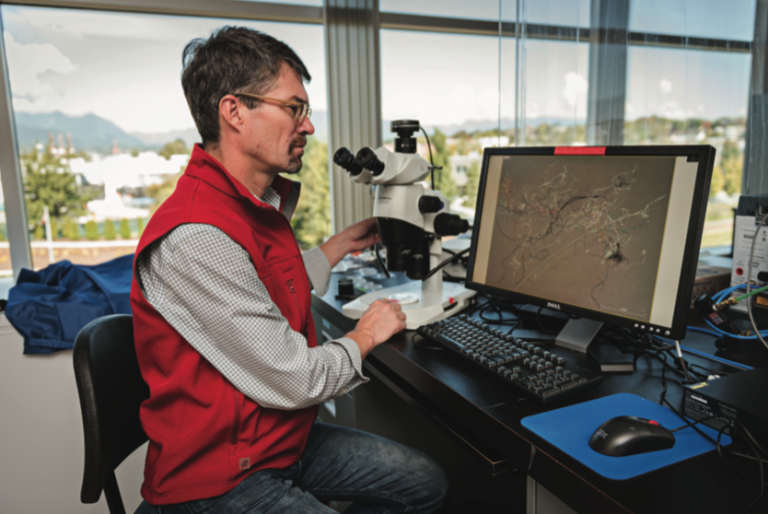

Peter Ross is vice-president of research at Ocean Wise, a global conservation organization headquartered at the Vancouver Aquarium, and the executive director of the Coastal Ocean Research Institute. He oversees 10 research programs at Ocean Wise, with a focus on conservation science. An international authority on the subject of ocean pollution, Ross launched the Ocean Pollution Research Program in 2014, with a strong focus on microplastic pollution in the world’s oceans. Here he explains his work and why it’s so important.

On the aims of the Ocean Pollution Research Program

The Ocean Pollution Research Program aims to deliver science-based guidance on the source, fate and effects of priority pollutants in the ocean. Topics of particular interest for us include the safety of traditional seafood for coastal Indigenous communities, the recovery of endangered species that are vulnerable to pollution, oil spill science and plastic pollution. Enabling positive change through meaningful research is what we hope to achieve.

On the sources of marine mircoplastics

Microplastics are an emerging threat to the world’s oceans. Microplastics refer to any plastic particle smaller than five millimetres in size and include both primary microplastics (designed to be small, as with microbeads), and secondary microplastics (fragments from larger plastic items). Microplastics are being ingested by zooplankton, small fish and other species at the bottom of the food chain, where they may block, damage or artificially satiate those speices. We have found that microplastic pollution is dominated by fibres, with evidence pointing to laundered clothing as a potentially important source of these. We are now working with major apparel retailers to deliver informed guidance on how best to address microfibre shedding from textiles.

On where marine microplastics are being found

Microplastic consists of particles of different densities, and these particles can also be weathered or ‘fouled’ in the environment. These features dictate how the particle will move through the environment, and where it will end up. For example, PVC is heavier than both fresh- and saltwater, meaning that it is likely to end up in sediments at the bottom of lakes, rivers and oceans. Polystyrene is lighter than water, meaning that it will typically float on the surface, where it can remain for a long period of time, or land on our shores. Most microplastic particles, though, have densities close to the density of seawater, and may be considered neutrally buoyant. This means that aquatic environments have particles throughout the water column, where they may be mistaken for food by grazing invertebrates or fish.

On the destructive impacts of microplastics on marine life

We know that large items of plastic can entangle, suffocate, drown or cause starvation in charismatic species, including sea turtles, seabirds and marine mammals. Increasingly, scientists are seeing that creatures of all sizes are ingesting plastics. Although evidence of harm is difficult to document in the real world because weak, sick or dying individuals are quickly predated or scavenged, lab-based evidence points to effects of microplastics on reproduction, growth and survival of invertebrates or fish in controlled conditions. More research is underway to address this important topic.

On the threats of microplastic pollution to people

There is increasing evidence that people around the world are ingesting microplastics through food, beverages and water. Questions remain about whether microplastics can break down into tiny particles that may then move across the gut and into circulation or tissues where they may cause harm, or whether any endocrine disrupting chemicals hitchhiking alongside the plastics may be available for uptake. The World Health Organization recently concluded that there is no evidence that microplastics represent a major human health threat. We will need more data to substantiate that perspective, with precaution dictating the need for action.

On reducing plastic waste

The single most important thing that we can do to reduce plastic waste is to close the loop on the plastic economy. This does not mean to stop making things of plastic, but it does mean fundamentally changing the way in which we design, build and manage our plastic economy. Improving recyclability through more sustainable designs, expanding alternatives to single-use plastics, improving recycling systems, creating aftermarket opportunities, tweaking wastewater treatment systems for homes and cities, and creating a powerful enticement for innovators.